The Adventures of Cuthbert Tattersall is the most anticipated game of 2017. By me. No one else knows about it. Or – knew about it. I guess you know about it now.

Gosh, the expectant audience for this whole project just doubled, that’s a bit unnerving.

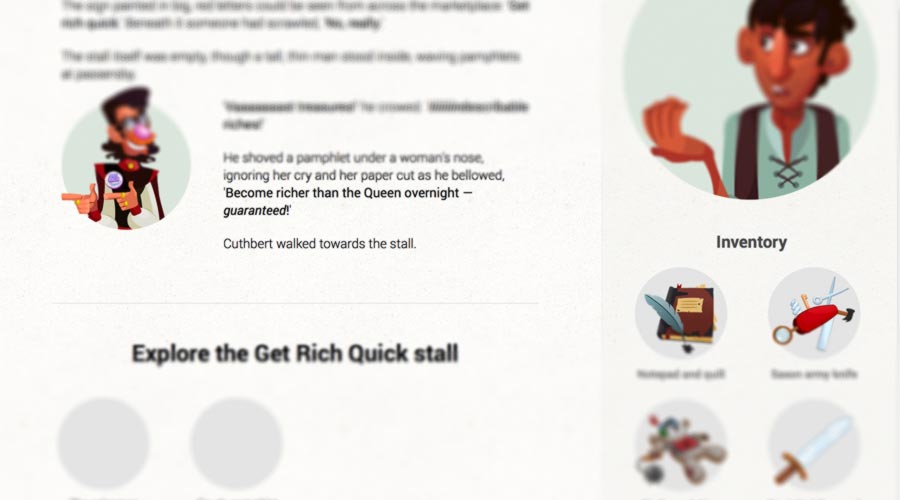

Cuthbert is a project I’ve been working on on-and-off for the past few years. It’s a text-based game, equal parts point-and-click and Choose Your Own Adventure book, which gives away both my age and my unwavering belief that we’re yet to leave the nineties.

I’ll never let go, Jack! Wikimedia Commons

I’ll never let go, Jack! Wikimedia Commons

It’s the sort of game I want to play; I love adventure games – Monkey Island, Grim Fandango, Broken Age, Telltale’s incredible Walking Dead and Game of Thrones series… In fact, the first video game I ever played was Maniac Mansion.

Of course, I was five years old at the time, so ‘played’ might be a bit of a generous term for spending twenty-nine minutes deliberating over which characters to send in before immediately getting caught and thrown in the basement. (The next game I played was Bubble Bobble and I was better at that; blowing bubbles and eating fruit were skills I’d already mastered.)

I got this. DollarPhotoClub

I got this. DollarPhotoClub

But as much as I love taking on the role of a mighty pirate or anthropomorphised rabbit or archetypical teenager who I’ll never break out of the basement, I often find adventure games can be a little… frustrating.

I don’t mean the frustration of trying to work out a puzzle (that’s the frustration you’re paying for); I mean the insidious frustration that seems to come with adventure games, the maddening frustration when you know you’ve got the right solution to a puzzle but the game needs items to be combined in an extremely precise order to be able to solve it; the tear-your-hair-out frustration when an item in your inventory is needed for something else later, so you need to go on a wild goose chase to find something entirely interchangeable with what you already have to solve a puzzle. If you even realise your first instinct was right at all and don’t struggle in vain to come up with an entirely different solution.

Wait… I got this. DollarPhotoClub

Wait… I got this. DollarPhotoClub

Then there’s the let down. That might be worse than the frustration. That deflating feeling when a puzzle is ruined for you when you stumble across crucial information in a conversation tree the game expected you to get to later, so you don’t really feel like you solved anything. Or when a game promises you your decisions matter and it’ll shape the game to your choices, like an old Choose Your Own Adventure story. And it doesn’t.

We all knew this was coming… Telltale Games

We all knew this was coming… Telltale Games

I was blown away when the first episode of Walking Dead pushed me into an impossible decision, save one person’s life at the cost of another. I was disappointed when, in the next episode, it became clear that my decision hadn’t changed a thing. The story was always going to unfold the same way, regardless of what I did; I couldn’t have any real impact on where my ragtag group of survivors went, what trouble we avoided or fell into. Even hurting people’s feelings didn’t stretch that far.

Now, I understand why I couldn’t do that. I don’t think it makes it a bad game. But it doesn’t make it the game it said it would be: one which would change because of my choices.

It’s a limitation of the genre; it’s a limitation of making games professionally. If you don’t have limited options, how can you test everything’s working, how can you ship it out on time?

A far-reaching game where your interactions with a character could drastically affect the story, where someone not liking you means they’ll refuse to help you and you’ll need to find another solution to the puzzle, where ‘so-and-so will remember that’ means they actually will remember that, and you can use the stick that’s already in your inventory instead of hunting high and low for a slightly different stick might be impossible when you have shareholders to report to and deadlines to meet, and you’re rendering graphics and hiring voice actors, and making something that works across every popular console. And several unpopular ones.

But maybe you can make a game that works like a Choose Your Own Adventure story if you… well, if you make it work like a Choose Your Own Adventure story.

I decided to find out if I could do it.

This is that.

Version 0.1: Tilt-a-whirl.

Version 0.1: Tilt-a-whirl.

This year, I hunkered down to finally build the game I’ve been talking about building. It’s something I’ve flirted with before – coquettishly plotting outlines and writing scenes, wantonly building unsustainable experimental game engines. Fluttering my eyelashes at it. But other projects kept coming up and I couldn’t find time to dedicate to it.

Then – out of nowhere – I turned thirty. I don’t think anyone expects something like that to happen to them but, let me tell you, when it does, it gives you some real perspective on what matters in life. Making games about comically inept heroes-in-training in a land of fairy tale creatures.

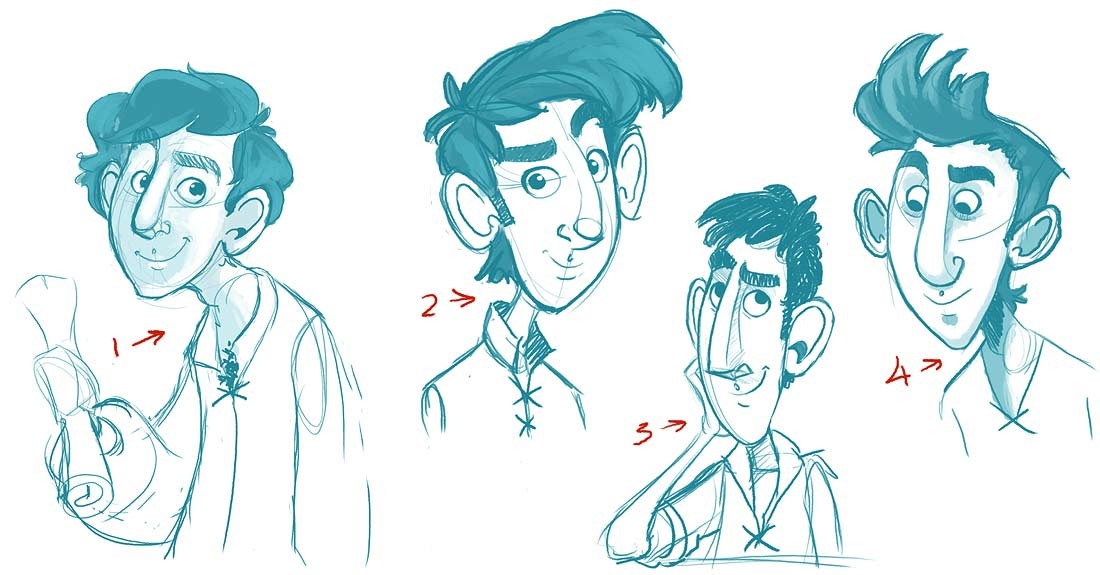

Teaming up with L. Whyte, incredible drawer-of-things, I decided to give myself two years of lunch breaks, late nights and weekends to write, code, and create the first half of the game. (It’s more impressive than it sounds.)

And I started this blog to shame myself into actually doing it.

Welcome to day one.