I bought Jolly Rover because: a) I had a few quid left on a pre-paid credit card and nothing else to use it for, and b) a point-and-click adventure game about pirates who are also dogs sounded hilarious.

I regret buying Jolly Rover because: a) I could have spent that money on something much more entertaining, like loo cleaner, and b) a point-and-click adventure game about pirates who are also dogs is exactly as bad as it sounds. And nowhere near as funny.

Spoilers ahoy!

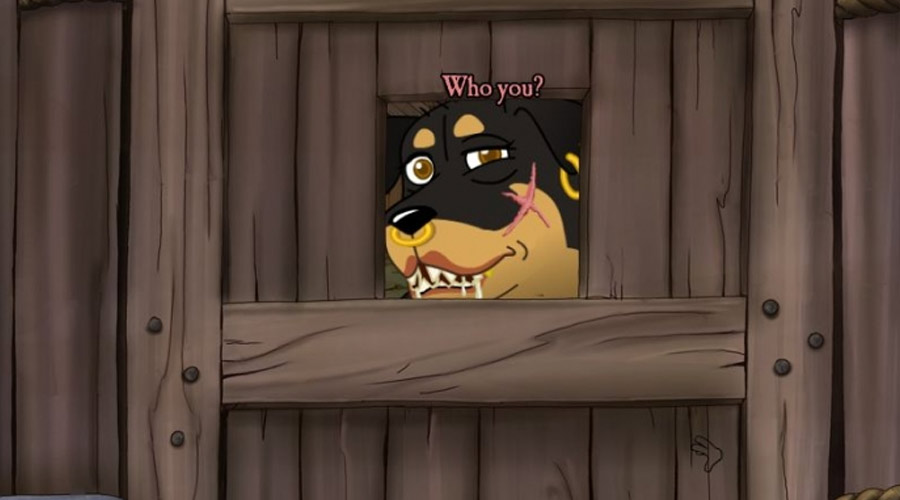

The game starts with your character, Jolly Rover, who’s some sort of rum producer, being kidnapped by pirates. You escape and get back to town, where Silvereye, the crooked… something – governor, maybe? Sheriff? He lives in a fort – insists you’ll need to pay if you don’t have your rum quota.

Dog politics. Don’t question it.

Just don’t question it. Brawsome

Just don’t question it. Brawsome

So you try to convince the pirates who previously kidnapped you and stole all your worldly possessions to hire you as their chef. (You may have killed their old chef in your escape. It got dark.) You spend approximately five-thousand years making soup, then wake up on Cannibal Island, where the pirates have sent you to see if there really are cannibals. (Negating the point of making the soup at all, if ‘human sacrifice’ was their plan for you all along; I wouldn’t expect that position to need a long CV.)

Using the power of voodoo to solve the same problem against slightly different backdrops, you find the cannibals and discover they’re – gasp! – women! And also not cannibals – apparently they disguise themselves as cannibals for mumble-mumble-reason.

One not-cannibal, Clara – daughter of the notorious pirate DeSilver – agrees to come with you after you find her father’s old pirate ship (and also raise his ghost from the dead; dog politics). Travelling to Clara’s childhood home, you repeatedly solve navigation puzzles until you’re attacked by Silvereye, who monologues about how he sold his soul to kill his brother, DeSilver (which feels like a bad eternal-soul-to-short-term-gain exchange rate, to me), and how he’s going to steal Clara’s soul, then promptly leaves you on a deserted island with all of your belongings, in a situation you can clearly escape from. Rather than killing you.

In fairness, he didn’t have another soul lying about. Though he did have a big sword. Which he used to knock you unconscious.

Rather than as a sword.

Pictured: no obvious use. Adobe Stock

Pictured: no obvious use. Adobe Stock

You, of course, escape the island – though not before you sit through a dream sequence where you juggle with the ghost of your dead clown father – and get to Silvereye in time to save Clara. Through the power of juggling.

Your juggling is, however, too powerful and causes a cave-in. But, in the game’s last and most obnoxious puzzle, you have all the pieces you need to create a hot air balloon to escape. After you teach your character what a hot air balloon is.

Then you and Clara sail off into the sunset, making vague sexual innuendo as the credits roll.

The game comes across as if someone watched a let’s play of the first two Monkey Island games and took notes. There’s a crazy hermit, a ghost pirate, a lot of voodoo, an island full of cannibals, a dream sequence with your dead father that reveals the answer to a puzzle at the end of the game, no less than two puzzles involving mucking about in chef’s kitchens, and a female pirate love interest. Though the writer looked at Monkey Island‘s Governor Elaine Marley – an intelligent woman who rules an island of rowdy pirates with an iron fist (and herd of piranha poodles), a kick-ass pirate in her own right who saves herself, thank-you-very-much – and decided the modern-day answer to that twenty-year-old character was Clara.

Ruddy Clara. Brawsome

Ruddy Clara. Brawsome

Clara. Who does exactly nothing, in the entire game except be seduced by your character’s weirdly sexist innuendo.

For something released in 2010 – and especially something that seems aimed at a younger audience – that really threw me.

And, I’ll admit, that’s my biggest bone to pick. The terrible dog puns, the lead character’s not-quite-explained-enough past, the easy puzzles (and the wholesale recycling of them), the I-wish-I-hadn’t-signed-that-contract voice acting – I could forgive it all if it didn’t come across as weirdly sexist.

First of all, we don’t meet a female character until we’re two thirds of the way through the game. Two thirds! They couldn’t have chucked some girls on the pirate ship? They couldn’t have made Jolly Rover miss his world-famous clown mother? They couldn’t – and this is going crazily out of the box – have made the main character Jolly Roverette?

And – yes, yes, I know – the main character in my game is a boy, cue the kill-the-hypocrite pitchforks. But I am working to keep the gender scales balanced. I actively keep count of my characters – their gender, their ethnicities, their ages – so I can see if some people are being represented more than others. I think it’s important that not every character in every game or book or TV show could be played by Chris Hemsworth.

Yeah, Thor. I’m metaphorically limiting your career choices. You wanna fight about it? (Please say no.) Paramount Pictures

Yeah, Thor. I’m metaphorically limiting your career choices. You wanna fight about it? (Please say no.) Paramount Pictures

And, having seen a game made in the last ten years that got it so wrong, I’m a little more secure that my weird gender count spreadsheet is a good thing.

Not that Jolly Rover didn’t have some good points. It had an in-built hint system that you picked up as part of a puzzle. Sam and I didn’t have to use it in the end, but since I’m going to the trouble of building an in-game hint system, it’s nice to know other people like them, too.

It also allowed players to solve some puzzles (well – skip them, really) by paying pieces of eight, which you could find scattered across different rooms. It was interesting, given I’m trying to do a if-the-object-makes-sense-I’m-not-going-to-make-you-find-a-microscopically-different-one-for-no-reason thing in Cuthbert. The problem with paying the pieces of eight, however, is it’s not clear that you’re skipping a puzzle. We wound up missing out on gameplay because we assumed giving the person the item they were asking for, which we already had, right there in our inventory, was the right thing to do.

It’s a handy lesson, for someone trying to be a game developer – sometimes the box is there for a reason. And that reason is not to infuriate your players by going wildly against their expectations.

It’s a shame. Jolly Rover should have been a fun, light-hearted set-up. The problem is, in modelling itself so much after Monkey Island – and there are nods in the game that make it clear that’s intentional, like the famous, ‘That’s the second-biggest (random thing here) I’ve ever seen!’ line – you can’t help but compare it. And find it wanting.

Monkey Island is – still – one of the best adventure games ever made. It’s at the top of the genre, but that doesn’t mean you have to hold every other game up against it. (Or so I desperately hope.) But if you deliberately stand in its shadow, it’s hard not to notice.

In the end, I don’t think I learned much from playing Jolly Rover. Don’t try to be Monkey Island, because you won’t be? Don’t be sexist, it’s not 1953?

I feel like I knew all that already.

But at least I didn’t have to clean the loo.