I’d like to write something about game development this week. Not my game’s development – why would I do that? – another game entirely: Thimbleweed Park.

For those of you who don’t know (hi Mum), Thimbleweed Park is a new game by the creative geniuses behind LucasArts’ Monkey Island and Maniac Mansion; for those of you who also don’t know what LucasArts’ Monkey Island and Maniac Mansion are… just… they’re good games, okay? They’re delightful point-and-click puzzle games with a lighthearted, laugh-out-loud sense of humour that makes playing them a transcendent joy which simply cannot be paralleled.

Except maybe by playing with some really fluffy puppies, but there’d have to be, like, at least four of them.

And they’d need to be wearing some darn adorable accessories. That matched.Adobe Stock

And they’d need to be wearing some darn adorable accessories. That matched.Adobe Stock

Kickstarted by fans, Thimbleweed Park is a must-play for anyone who had a computer and a lot of time to work out monkey wrench pun solutions in the nineties. It takes the same sense of humour and old school pixel art that the LucasArts games were famous for, and teams them with the modern advantage of bigger and faster computers, rendering the art with tones and shadows and using subtle animations to make everything feel more real.

It’s the game that the creators Ron Gilbert and Gary Winnick would have made twenty years ago, if the technology had allowed it.

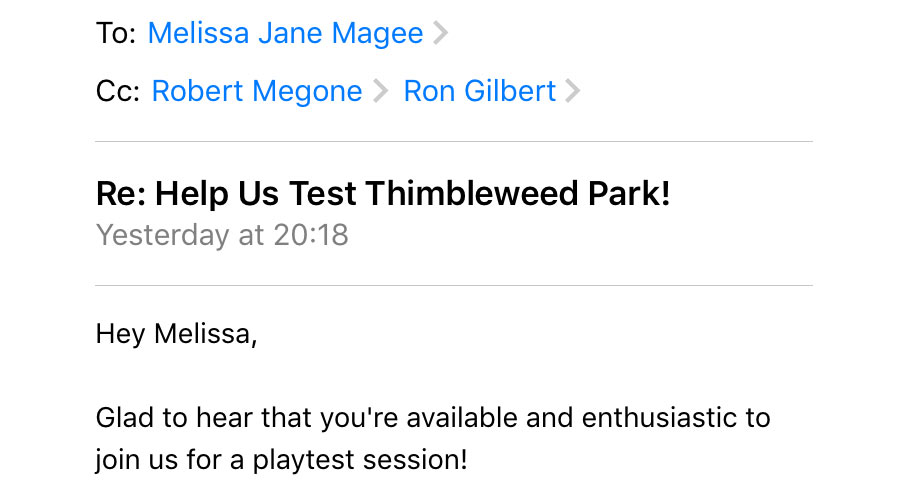

And I got the – extremely jammy! – opportunity to playtest it a couple of weeks ago.

The best CC to ever be CC’d.

The best CC to ever be CC’d.

Obviously, I’m not going to spoil anything – first, because I’m a not horrible person, and second because I’m a not horrible person who doesn’t want to get sued – but I do want to write up some of the things that really struck me (er, in generic, non-sue-y terms), because playing it was like taking a lesson in how to plan A Real GameTM.

The first thing I noticed was how the developers had prioritised what they were spending their time on.

Rooms which didn’t have anything important to the story (or important to the bits of the story I could reach in two hours and twenty minutes) were only rendered in black and white, without the final layers of colour and lighting. When we tried to interact with items in the unfinished rooms, they showed placeholder text – because we were looking at rooms we couldn’t advance the story in, and the developers had (presumably) wanted to put their attention where it was more needed.

On pizza toppings. Terrible Toybox, Inc.

On pizza toppings. Terrible Toybox, Inc.

And typos – typos were everywhere. Not big glaring ones, things like the word ‘start’ instead of ‘started’ and references to ‘mansion mansion’ instead of ‘Mansion mansion’ (…obviously). It felt like the sign of a game still in progress, still being tweaked and improved with feedback.

It was a good reminder that things don’t have to be perfect before you’re allowed to show them to people – especially since a second pair of eyes on your work will catch a problem you’ve missed.

Imperfections aside, there was so much to admire in how the team had constructed the game. It started with a mystery, and the mystery kept on getting bigger – not in the Simon the Sorcerer how-the-hell-do-I-solve-all-these-puzzles way, but in the there’s-so-much-more-to-this-story-than-what’s-been-let-on-I-can’t-wait-to-find-out-what way, and it was reassuring to see someone like Ron Gilbert following the same storytelling principles I’ve been sticking to – start in action, raise some questions, fill your game with drunk hobos and swearing clowns…

Pictured: storytelling! Terrible Toybox, Inc.

Pictured: storytelling! Terrible Toybox, Inc.

What was really interesting was how subtle they decided to be with some of the storytelling – I’d just accepted that the two interchangeably playable characters, Agent Ray and Agent Reyes, were who they said they were. Then I checked their notebooks. (Then I started questioning their suspiciously similar names.)

Having important information only appear outside the normal gameplay seemed interesting – if dangerous. Maybe the idea is to reward more vigilant players; the backstory will come into the main action eventually (I got hints to the slightly-less-sinister-than-I’d-been-imagining nature of one of the agents’ motives as they talked to some of the… interesting people in town, and I imagine it will all come out in the open as the game goes on). But players who diligently work through all the available Look At descriptions are rewarded with more understanding, with early hints and jokes.

It’s a way of exploring the interactivity of games and playing with non-linear storytelling. Not one I think I’m necessarily brave enough to adopt, but interesting nonetheless.

And that experimental storytelling carries on – as you speak to people, they explain more about the history and the people of the town. You get told about other characters – but instead of just hearing the story, you play as that character in a flashback.

Pictured: storytelling! Terrible Toybox, Inc.

Pictured: storytelling! Terrible Toybox, Inc.

It’s an inventive way of keeping the story interesting while getting a lot of information across, and it was nicely reassuring to see big names in the game industry don’t shy away from telling stories in new and interesting ways.

Especially since they don’t get much more ‘interesting’ than how I’m doing Cuthbert…

I can’t say anything else about Thimbleweed Park without getting into specifics, and I don’t want to spoil anything – it’s a great game, and definitely worth playing when it comes out next year.

I keep thinking over the gameplay in my head, wondering if my suspicions are right, wondering where the story’s going. And hoping I can do something half as good with my own. (I’d prefer to make it twice as good, really, but I’ll take what I can get.)