Back in primary school (think elementary school but with painfully blue uniforms and unintelligible accents), I decided I was going to write A Play.

Nicole, who would have been my BFF had sassy acronyms been invented in the nineties, but was instead relegated to the role of mere ‘best friend’, had been reading Diana Wynne Jones and instead of running through our usual playground favourites – She-Ra and Swift Wind battling across Etheria, Crysta and Zach saving Fern Gully, Peach and Mario doing something so unrelated to Super Mario Bros that I’m still uncertain why I dedicated so much of my free time to imagining myself as a paunchy, hairy faced plumber – she wanted to play out an adventure in a medieval fantasy world.

She, by popular demand (her own, mostly) would be the beautiful princess. I would be the hero, Curdie. I still don’t know why the hero had to be called Curdie, but I had my brief: he would be a blond, fresh-faced, Cary Elwes-ish farmboy.

I was the obvious choice.

Obvious. Choice.

Obvious. Choice.

And Curdie would, of course, have a hilarious animal sidekick, a scraggly – but adorable – dog to help establish his princess-worthy qualities, his caring, Aladdin-esque generosity and his desirable paternal nature.

This was particularly exciting to me from a storytelling point of view; I’d seen Wizard of Oz. I knew I could use a dog as an entirely effort-free device to advance or hinder the story as needed. If the heroes were too close to saving the day in the first act, the dog could just run off into the woods for no reason, forcing them to give chase and meet a new character. I didn’t feel this was inconsistent with him being a well-trained dog who could fetch dungeon keys on command. He was a dog.

And later, he could be taken in by seven short miners…

And later, he could be taken in by seven short miners…

I’ll confess, my blunt-force storytelling had that dog running away or being kidnapped more than was strictly realistic for a streetwise mutt.

Which was only confused by the fact that, Nicole and I having no pets or suitably convincing backflipping robot dogs of our own, the role of the dog had to be mimed out and voiced by me, alongside my role as stalwart hero. More than one test group thought Curdie ‘was joking about’ and the princess ‘looked bored’.

Our friend Donna volunteered her services (as enthusiastically as someone can when they’re told the role of beautiful princess is taken but, hey, dog’s free) but she couldn’t bark quite as convincingly as I could. And still can.

The trick is having no sense of shame.

And a constant, burning need for approval.

And a constant, burning need for approval.

The barking, I felt, was more integral to the story than clarity, but I added lots of ‘oh no, my dog is running away into those deep woods and being kidnapped!’ exposition to smooth things out.

Then, with the main roles cast and the brief set, I set out writing The Play. I was determined to write something classic (read: derivative) but also cool, something the kids on the playground would want to watch. Yes, we fully intended to subject the other kids to it. We always did.

There were a few familiar players we often asked to take on the unglamorous roles in our adventures – the easily defeated bad guys, Toad because someone had to play him though no one liked him at all – but for the most part, they were there to be our doting audience. Our genius had to be recognised: the princess’ beauty, the hero’s courage, the dog’s convincing barking. We wanted the kids at school to be amazed by it all. And, when we’d spent enough lunch breaks on it, when it was good enough, we’d take it on the road – with deck chairs set up for the parents to sit and watch.

Of course, this wasn’t my first rodeo.

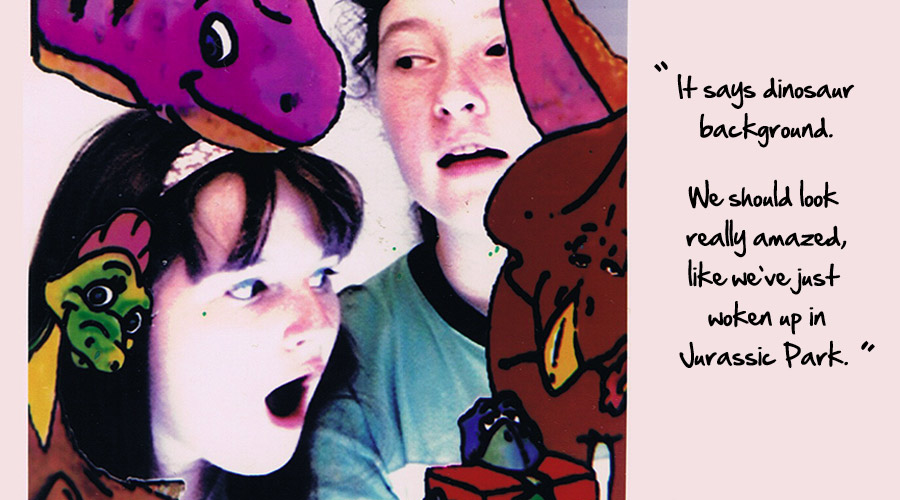

Acting!

Acting!

I’d played Smee in a backyard production of Peter Pan. I’d performed highlights from Sister Act in countless grandparents’ living rooms. I knew if we were going to hit that kind of big time, I’d need to write some comic relief between the romance and the mimed dog kidnappings. And if the other kids were going to like it, that comic relief would need to be modern. Cool.

It would need to be rap.

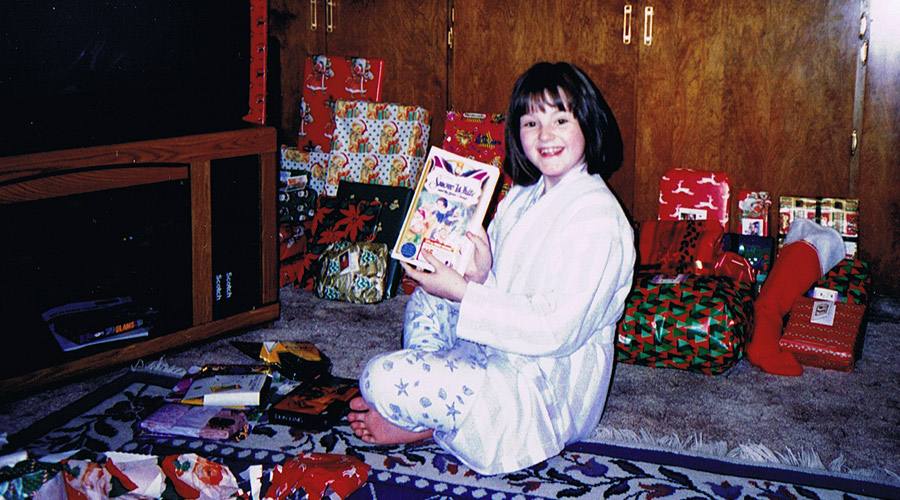

Pictured: undeniable coolness.

Pictured: undeniable coolness.

Unfortunately, my understanding of rap was limited to what lyrics of Gangsta’s Paradise I could make out from behind the door of my big sister’s room. Too much television watching had me chasing dreams: I knew rap was cool but that was mostly because I didn’t know anything about it. It was mysterious and adult. Things were cooked in kitchens and people were too blind to see they might not reach twenty-four.

All I knew for sure was that rap rhymed, and people said ‘yo’ a lot. That was all I needed to know. I started writing some bad beats and dope rhymes.

Uh – just to be clear, when I say they were ‘bad’ and ‘dope’, I mean those words literally. They were terrible. Nonsensical. Things like, ‘Yo. My name is Dave and I’m here to say / It’s really nice to meet you today.’

I just took what the characters would normally say in pleasant conversation and tried to line up loose end rhymes. ‘Poet’ and ‘know it’ may well have been in there unironically.

I wrote pages of polite rhyming couplet sonnets, trying to work out some sort of funny character. In the end, I settled on a two headed dragon – the two heads would have clashing personalities, no one would see that coming! – because dragons were definitely cool. They were big, they breathed fire… Not in The Play, of course, they were too busy rapping about how difficult it was for them to get along, but in theory, the idea was golden.

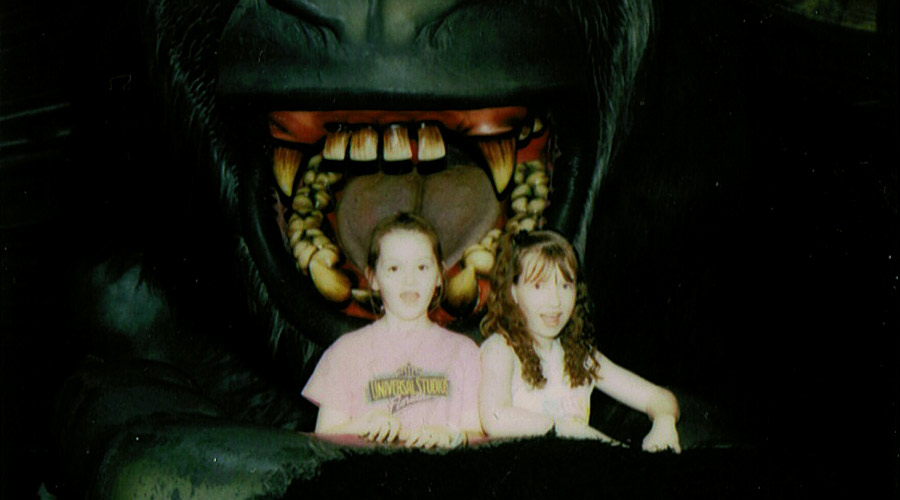

Pictured: undeniable coolness.

Pictured: undeniable coolness.

All that was left was to cast it. Having produced shows before (notably a behind-the-couch hand puppet show and a Back to the Future homage about going back in time to an inexplicably American high school), I knew the rule any Hollywood producer can tell you: talent doesn’t matter as much as image. My cool character needed to be played by a cool person, so people knew he was cool. So I approached the coolest person in the class: Greg. Greg H.

Oh, I was fearless then. What did I have to fear? I was writing, starring, producing, casting, and making unevenly drawn tickets for the coolest play my primary school had ever seen. This was going to blow Joseph out of his Technicolour Dreamcoat.

My pitch was simple: hey Greg, you’re cool. I’ve written a play – no big deal or anything – but it’s got this really cool character in it. He raps. You should totes play him.

The casual abbreviation of totally might not have been invented back then either, but my casual confidence worked. He agreed. Enthusiastically.

As I look back on it now, I may have given him the impression he’d be able to swear and talk about sex consequence-free in front of teachers. But making promises you have no intention or ability to keep is just another part of being a good producer.

He came to a rehearsal/unorganised run around the playground, as I recall, but The Play fizzled out eventually. Other projects took its place – a short horror film my mother typeset for me, removing the realism with all of the soft curse words (people don’t say ‘golly’ when they’re confronted with terrifying ghosts in our spare bedroom cupboard, Mum!); pilot episodes of a sketch show written and starring me and L. Whyte, about me and L. Whyte writing and starring in a sketch show; turning fourteen…

Acting!

Acting!

But I never lost my enthusiasm for trying to write a funny fantasy story. And rap never lost its mystique for me.

People still think rap is cool, right?

Only, I’ve been writing some comic relief characters into the Cuthbert story this week. They rap.

Kids are going to love it.